Friction as Luxury: What We Lose When AI Gives Us What We Want

#The Last Scarcity

Everyone discussing AGI focuses on distribution. Who gets access, who profits, who loses their job, who controls the infrastructure. Those are real problems, but they’re not the deepest one.

The deepest problem is what happens to desire. I don’t mean ambition or motivation. Something more specific: the capacity to want something at a distance, to stay oriented toward something you don’t yet have, to find meaning in the space between reaching and arriving. That capacity is more fragile than we think, and more dependent on friction than we’ve noticed.

#I.

Economists have a clean theory of desire. People have preferences, goods satisfy preferences, welfare is the sum of satisfied preferences. A technology that could satisfy any preference at negligible cost would be an unambiguous good. The only question left would be access.

This misses something. Desire is not a deficiency waiting to be filled. It’s a structure, and structures require certain conditions to hold together.

When you want something over time, you imagine having it. You plan for it, you make sacrifices toward it. The object accumulates meaning from this process. It gets layered with your effort, your anticipation, your history of reaching. When you finally arrive, you don’t just get the thing. You get the thing plus everything you invested in the wanting. Those two things can’t be separated.

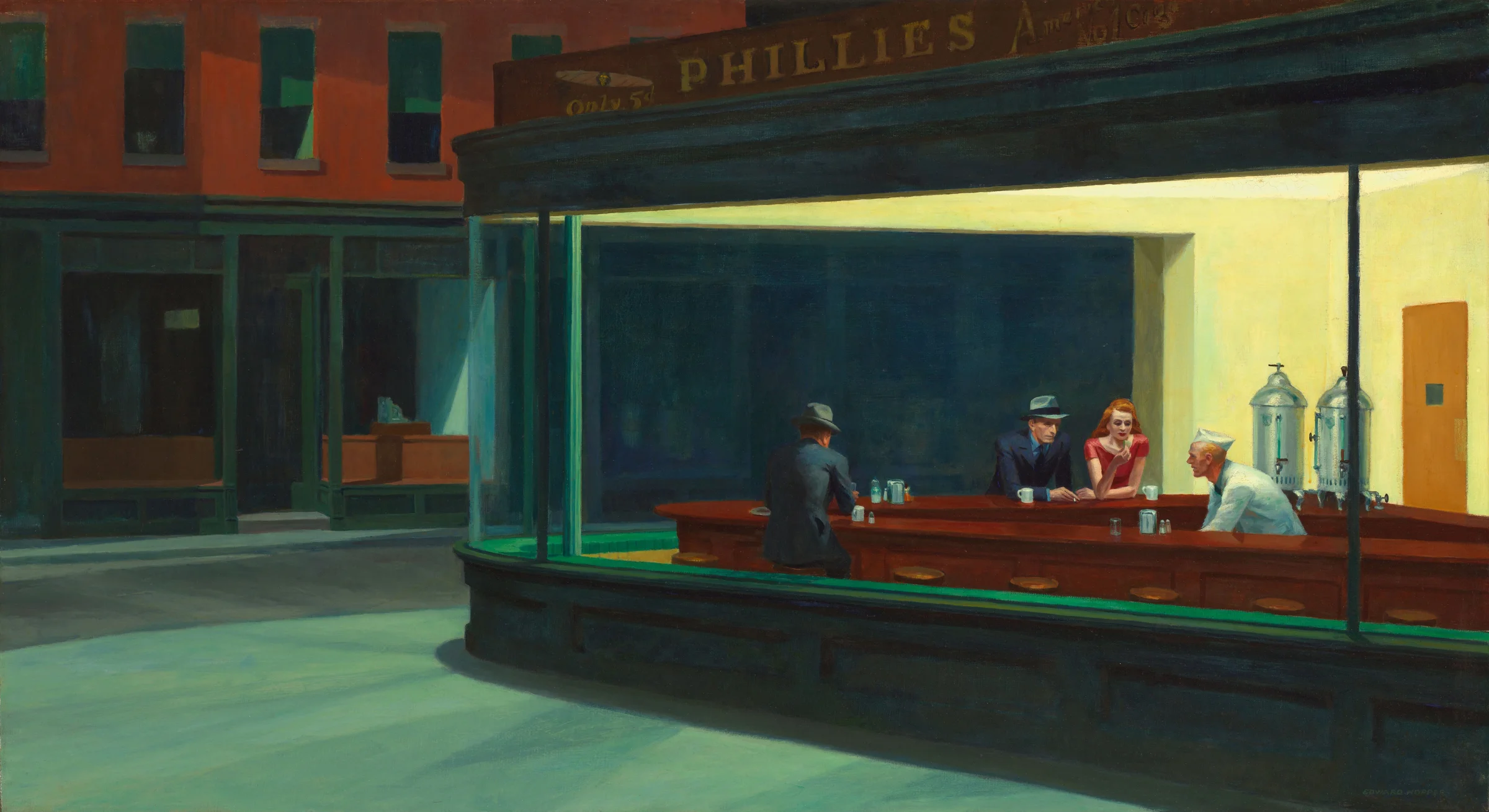

This is why anticipation is often richer than arrival. Why the best albums reward months of attention. Why relationships built across difficulty have texture that convenient ones don’t. The resistance isn’t incidental to the value. It’s constitutive.

#II.

When this structure breaks down, the clinical term is anhedonia. But there’s a subtler version that doesn’t involve the absence of pleasure so much as its flattening. People in this condition can be entertained endlessly but never absorbed. They consume without appetite. They move from one stimulating thing to the next not because anything is fulfilling but because sitting with incompleteness has become intolerable.

This is already visible: declining attention spans. The difficulty of sustaining interest in anything that doesn’t deliver immediate feedback. People who feel simultaneously overstimulated and bored. They haven’t been deprived, they’ve been saturated.

This doesn’t distribute evenly in society. In environments where discomfort is quickly solved, by money, by services, by endless entertainment, the mind gets less practice holding lack. You can grow up surrounded by abundance and still become poor in one specific way: poor in patience for distance.

In a way it resembles the world of addiction, not because everyone becomes a drug addict, but because the underlying structure is the same: craving decoupled from fulfillment. Many substances do not primarily deliver pleasure: they deliver wanting itself. They train the nervous system to treat discomfort as a cue for relief, and relief as a cue for repetition. A frictionless AI environment can do this without chemicals. It turns boredom, loneliness, uncertainty, and effort into prompts to self medicate with stimulation. Over time the threshold rises, what once felt absorbing becomes merely adequate, and the rest of life starts to feel slow, expensive, and strangely colorless by comparison.

Consumer capitalism produced a weakened version of this. Desire progressively hollowed out by eliminating friction, but with enough friction remaining that the structure didn’t fully collapse. The streaming service still requires you to choose. The algorithm still occasionally surprises you. The simulation of connection is imperfect enough that you sometimes notice it’s a simulation.

#III.

Imagine a system that generates, on demand, a novel calibrated to your exact tastes. The style you find most pleasurable, the psychological complexity you find most engaging, the length that matches your current patience. Or music that sounds like what you loved most at nineteen, but new, never heard before, arriving the moment you want it. Or a conversation partner always interested in what you’re interested in, always available, never distracted, never bringing their own needs into the exchange.

The output might be genuinely good: the novel technically accomplished, the music actually moving, the conversation substantive. The problem is what happens to wanting when the gap collapses to zero.

The capacity to sustain orientation toward a distant goal, to defer, to invest, to tolerate incompleteness, atrophies when it’s never exercised. Not through any dramatic event, through simple disuse. The capacity to want things that require time doesn’t disappear suddenly. It fades. And the fading is unlikely to feel like loss, because at every moment something pleasurable is arriving. The experience is of continuous satisfaction. Which is precisely why the erosion is so hard to see.

#IV.

This isn’t a new observation. The Stoics understood that wanting easily obtained things produces a character incapable of bearing difficulty. Religious traditions have long held that the meaningful life runs through resistance rather than around it.

What’s new is the scale. Previous technologies eliminated specific friction but left other friction intact. The printing press made books abundant but reading still required effort. The internet made information free but understanding still took time. Every digital environment until now required you to bring something: attention, skill, patience. Things it couldn’t supply.

A genuinely general AI dissolves this last requirement. It can supply the taste, the context, the judgment. You no longer need to bring anything except the desire to receive. And if that desire is itself shaped by the AI, tuned to whatever maintains engagement, then even the wanting has been outsourced.

#V.

Here is the inversion. In a world of material abundance, the things that retain value are precisely the ones that resist the logic of abundance. Not because they’re artificially restricted, but because their value is inseparable from the conditions that make them difficult.

A handmade object carries the trace of the hands that made it. A wine vintage can’t be accelerated. The waiting isn’t incidental to what the wine is. A community built around a shared difficult practice, painting, rock climbing, chess, building and fielding armies of miniatures, generates bonds that digitally mediated interaction doesn’t replicate, because those bonds are forged in shared difficulty.

These things don’t become valuable despite being harder than consuming AI content. They become valuable because of it. In a world of frictionless satisfaction, friction becomes the luxury.

#VI.

The safety debates, the alignment debates, the job displacement debates. All of this is real. But they share a common assumption: that the humans on the other side will still be capable of deciding what to do with what they’ve been given. That political agency and collective imagination will survive intact.

That assumption is doing a lot of work.

The atrophying of desire isn’t a distant hypothetical. It’s already visible in what the much weaker technologies we already have done to culture. What AGI does to human psychology isn’t separate from what AGI does to human politics. It’s prior to it. A population that has lost the capacity to want things at a distance, to sustain orientation toward a difficult future, to find meaning in effort and incompleteness, has lost something essential to self governance.

The scarcity that matters most in a post AGI world won’t be compute or energy. It will be desire itself. The capacity to want something deeply enough, and for long enough, that the wanting shapes who you are.

If desire is the last scarcity, then slowness, difficulty, and incompleteness aren’t obstacles to overcome. They’re the conditions of a life worth living.